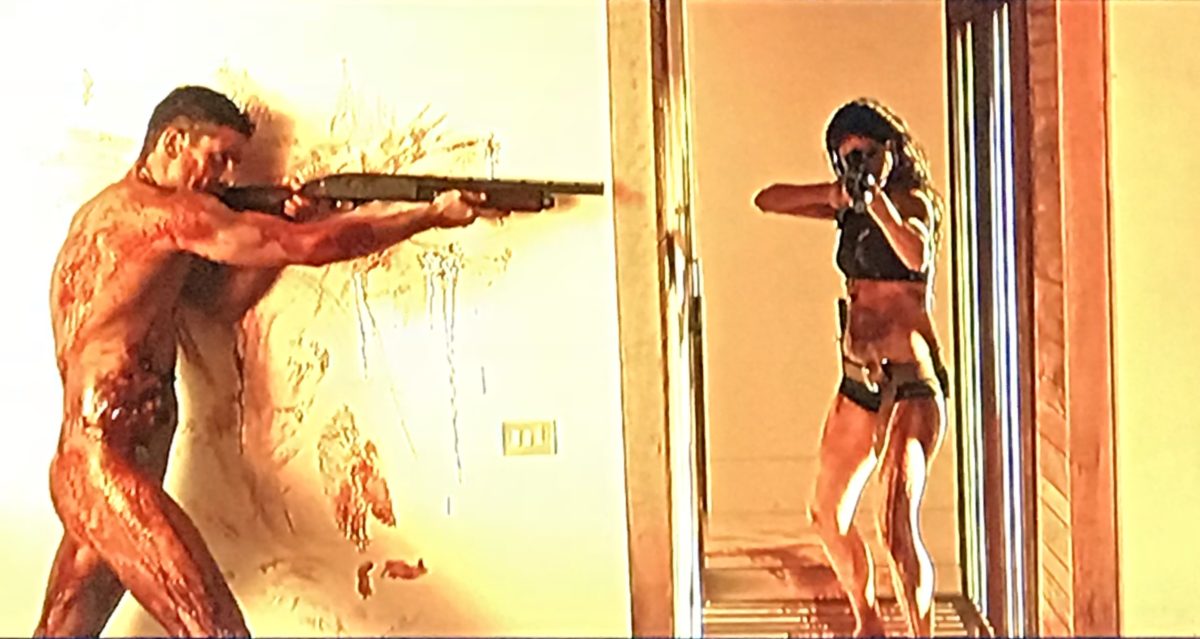

Revenge, dir: Coralie Fargeat, 2018

Movie Notes: Revenge, dir: Coralie Fargeat, 2018

I love movies because they’re such good indicators of what’s going on in the collective consciousness.

We get to watch our deepest struggles, conflicts and concerns play out as literal projections on larger-than-life screens all over the world. And then we get to see where these stories take us as individuals – how they impact us, what they make us feel, where we stand in relationship to them.

These are our Greek myths, our Gods and Goddesses, our means of contextualizing present day life through the code of storytelling.

And so it should be no great surprise that 2018 sees a striking cinematic first:

An exploitation rape/revenge fantasy written and directed by a woman.

And, yes, it’s a brutal, convention-shattering movie that deeply reflects the ethos and momentum of the recent “time’s up” movement.

Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge is the rare rape/revenge movie that refuses to present the heroine as the very model of a virtuous, do-gooding, innocent young woman –

And also refuses to present the attackers as the kind of inbred hillbillies we see in something like I Spit On Your Grave or the psychopathic home invaders we see in something like Last House On the Left.

Those kinds of characterizations can be destructive for a number of reasons –

Chiefly because they subtly (or not so subtly) reinforce the idea that there are women who “deserve” to be raped and then there are those women who don’t deserve to be raped (good girls we can root for), that there are women who “deserve” to have our sympathy as assault victims and then there are those women who don’t deserve our sympathy as assault victims –

And it all depends on how they conduct themselves – what they wear, how they act, their overall character.

Meanwhile, using stock villains from the fringes of society allows viewers to subtly (or again, not so subtly) eroticize the rape because it is so far removed from the world we actually know –

In other words, these people are not like us –

Which means that we as viewers get to have our cake and eat it too:

We can secretly get off on the fantasy version of rape and then pat ourselves on the back for rooting for the (morally approved) heroine when she gets her vengeance.

It’s exploitation in the guise of a liberation narrative – which tacitly reinforces the very cultural attitudes that produce a movie like this in the first place.

The beauty of Revenge is that it blows all that wide open by providing us with a heroine who is the epitome of a woman who “asks for it” –

A flirtatious blonde who sleeps with married men, boldly flaunts her body and puts herself in potentially dangerous sexual situations…

And then Revenge asks us to see the injustice committed against her.

In fact, Revenge builds a whole dramatic narrative around the idea that our heroine has been unequivocally wronged and, even better, that we should be aligned with her sense of innate and total righteousness against her attackers.

And, in doing so, Revenge asks us to look at the cultural places where we would dismiss someone like our heroine as “asking for it.”

Meanwhile, her attackers are indeed men who inhabit our actual world – they live in nice homes, they’re married with children, they watch TV (ogling the models and getting amped up by aggressive wrestling)…

They are the product of, the participants in, and the agents of a culture that allows them to feel entitled to sex from a comely young blonde who puts it all out there.

They are on every street corner.

They are in every office.

They are in every sports bar.

In fact, all of the characters are introduced as an active part of this culture – both the men who commit the central crime and also our heroine who longs to go to LA to be “noticed” – a culture that hits very close to home, the same culture that created the Steubenville rape, the same culture that created the Brock Turner case –

And, for that very reason, this rape revenge “fantasy” is no longer such an easy fantasy.

And, for me, that is the simple and timely brilliance of a movie like Revenge –

It completely annihilates the built-in coding of the usual rape/revenge fantasy and instead places it squarely in the dramatic domain where it actually belongs:

Casual sexual entitlement, everyday sexual aggression and easy victim blaming.

A genre narrative has been shattered.

And from the remains we have a mirror reflecting the very cultural values that gave birth to this kind of film genre in the first place.

In other words, the “fantasy” isn’t so easy to swallow when it features some of the actual men of our world who rape (and get away with it) –

When it features some of the actual women in our world who get assaulted (and then blamed for it).

We can no longer get lost in the eroticized fiction of it.

We can no longer make excuses for our own enjoyment of it.

We can no longer ignore the movie’s impact on – and perpetuation of – the very thing that it pretends to condemn.

In the same way that Buffy the Vampire Slayer made a fearless heroine out of the vacuous blonde who typically gets killed early in the story, Revenge transforms the scapegoated sex assault victim into a mythic warrior.

Something has been reclaimed.

And though her bloody revenge might not be the best prescription for restoring sexual balance in our world, it is certainly a real and ferocious battle cry letting us know that time is indeed up.

Tags In

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Tags

Recent Posts

- How to Reframe Your Addictive Tendencies From a Place of Compassion

- What’s Got Monique So Triggered Around Candiace, Charisse & T’Challa…?

- A Quick Word On The Collective Shift Taking Place & How To Navigate It

- The Quickest Way To Your Higher Self Is Actually Through Your Lower Self

- A Jamie Stein/Monique Samuels Mash-Up for Your Viewing Pleasure…